- The Senate Committee on Rules and Administration debated advancing the DISCLOSE Act.

- If passed, the bill would require organizations to disclose donors who give $10,000 or more during an election cycle.

- Variations of the DISCLOSE Act were defeated in the Senate multiple times in the past.

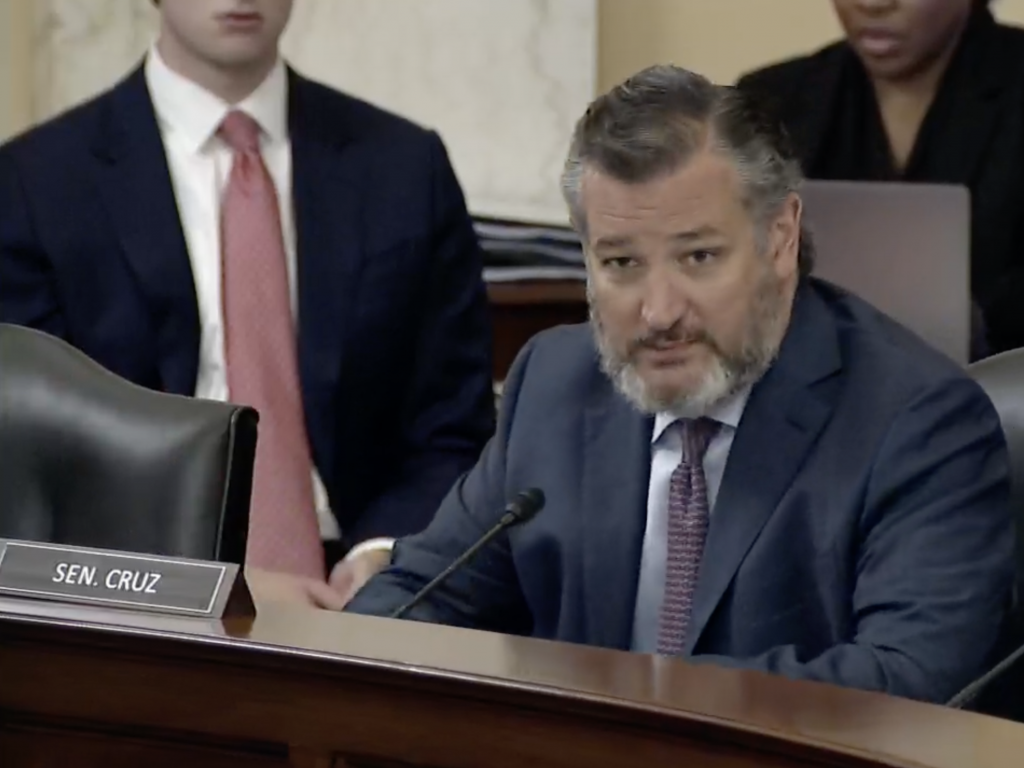

Calling it blazingly "unconstitutional," Republican Sen. Ted Cruz foreshadowed yet another defeat for Democrats' unrealized weapon against secret money in politics — the DISCLOSE Act.

"The DISCLOSE Act is designed to target and harass speech that the left doesn't like," Cruz said at a Senate hearing Tuesday.

As Cruz's comments indicate, most Republicans have no appetite for forcing politically active organizations to reveal the identities of their mostly wealthy donors, and the DISCLOSE Act is likely to again die this congressional session just as other versions have for years.

Conservatives argue that big-dollar bankrollers have a right to anonymously express their political views through campaign contributions, so long as they're not giving the money directly to candidates' own campaigns.

The DISCLOSE Act, as written, would require politically active organizations — including corporations, labor unions and independent political action committees — to disclose donors who contribute $10,000 or more during an election cycle. Most elected Democrats argue that unlimited political spending without transparency is corrupting.

Technically named the Democracy is Strengthened by Casting Light On Spending in Elections Act, the first DISCLOSE Act proposal first appeared a dozen years ago as Democrat-led response to the Supreme Court's 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

At the time, then-President Barack Obama criticized the decision as one that would "open the floodgates for special interests … to spend without limit in our elections."

Since then, so-called "dark money" — both from the left and right — has flowed into national political elections, often via "social welfare" nonprofit organizations and business leagues that are not, by law, required to publicly disclose their funders. Sometimes, they spend it themselves. Lately, they've been injecting it into super PACs — political committees that may raise and spend unlimited amounts of money, including from non-disclosing nonprofits, corporations, and unions.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, who sponsored the bill in 2010, said the Supreme Court's decision in Citizens United is "one of the most awful decisions we've ever had from the court."

The DISCLOSE ACT "should be bipartisan through and through, sadly it's not," Schumer said. "The American people have a right to know who is trying to influence the elections. Democracy cannot prosper without transparency."

David Keating, president of the Institute for Free Speech, a nonprofit organization that supports the deregulation of political money, testified Tuesday that the DISCLOSE Act would hurt people who exercise their legal right to participate in the nation's elections.

"Significant portions of the bill would violate the privacy of advocacy groups and their supporters – including those groups who do nothing more than speak about policy issues before Congress or express views on federal judicial nominees," he said. "Free speech can mean the difference between liberty and tyranny."

During the questioning, Sen. Angus King, an independent from Maine who caucuses with Democrats, tore into Keating.

"A person who contributes a million dollars to a political campaign, why are their tender feelings any more worth protecting than my $200 donor who has to be disclosed?" King asked. "The nub of your argument is fear of harassment of people."